Galápagos Penguin Project

Galápagos Penguin Project | Galápagos Penguin Biology | Study Site | Miti & Flecha | Youtube Videos

Where are they found?

Darwin never saw penguins during his visit to the Galápagos Islands. These small penguins tuck themselves away in lava tubes and rocky crevices, often escaping the human eye. Penguin eggs were found on the islands in 1906, and a few nests were discovered in the 1950s and 1960s. It wasn’t until 1970 that Dr. Dee Boersma, then a young graduate student starting her dissertation studies, discovered Galápagos penguins breeding at several sites on the islands. Boersma did her first head count of penguins around Fernandina and Isabela Islands in 1970, and another count in 1971.

The Galápagos penguin is the rarest of all penguin species and is categorized as Endangered on the IUCN Red List because of their small population and restricted distribution. The current population is likely somewhere between 1,500 and 4,700 penguins, which is suspected to be about half of what it was in the 1970s.

A young Dee Boersma in the Galápagos during a 1972 survey.

Research

The main focus of research on Galápagos penguins has been to determine the health and size of the population. Each year, Dr. Boersma and graduate student Caroline Cappello make two trips to the Galápagos Islands to measure and weigh penguins to evaluate body condition.

Alongside the Galápagos National Park and Godfrey Merlen, researchers check both nests constructed by the project in 2010 and natural nests during each visit. Although most penguins have not nested between 2010 and 2017, 32% of occupied nests were ones Dr. Boersma and her team constructed. Researchers also note any presence of juveniles in the population. If they find juveniles, this indicates penguins recently bred successfully. If there are no juveniles, the population is likely declining.

When weighed and measured, Galápagos penguins receive a web-tag, a small, numbered tag inserted into the webbing of their foot. This tag allows us to track individuals over time.

Recognizing the loss of breeding sites as a threat to the penguins, Dr. Boersma teamed up with the Galapagos National Park and Godfrey Merlen (right) in 2010 to build 120 nests.

Threats

The biggest threats to Galápagos penguins are climate change, introduced species, overfishing, and mismanagement of fisheries. Other threats include petroleum and plastic pollution, toxic algae blooms, disease, and the introduction of non-native plants that degrade breeding habitat.

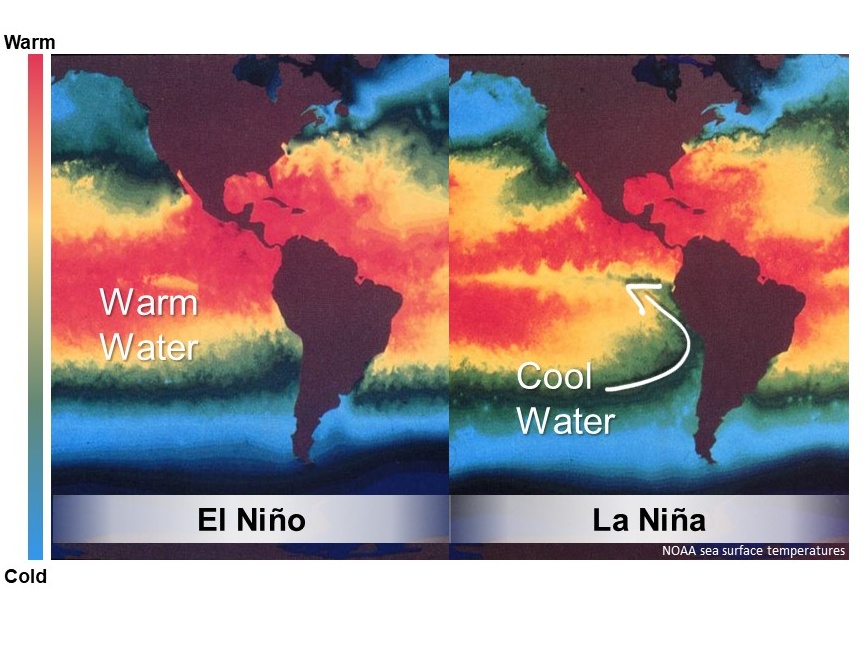

With climate change comes an increase in the frequency of El Niño events. During El Niño periods, surface waters are warm and food is scarce, so few penguins molt or breed. Severe El Niños may cause animals that depend on the productive upwelling to starve. The 1972 El Niño caused reproductive failure for the penguins and crashed the population of seabirds in Peru and Ecuador. The cold La Niña waters are rich in food, which can provide penguins with sufficient energy to molt, breed, and feed their nestlings.